Annual Bluegrass Weevil in Turf

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲Introduction

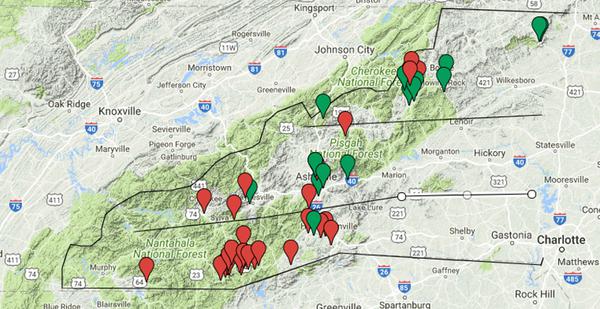

Initially identified as the Hyperodes weevil, the annual bluegrass weevil, Listronotus maculicollis, has historically been a destructive pest of annual bluegrass and creeping bentgrass on fairways and greens in the northeastern United States. It was first described as a turfgrass pest in Connecticut in 1931. Since then, it has spread south and west and has become an insect of concern for managers in western North Carolina (Figure 1).

Description

Annual bluegrass weevil adults (Figure 2) are dark brown or black beetles, approximately 1⁄8-in long with a pronounced, curved snout and have gray-yellow hairs and scales on the thorax and elytra (hind wings). ABWs resemble billbugs (Figure 3), another common turfgrass pest, but are much smaller (~1⁄3 size), their antennae attach to the tip of their proboscis (snout), rather than the base and their snout is shorter and stouter than that of a billbug (Figure 4). Larvae are cream-colored with red-brown head capsules, legless, and range from 1⁄25 to 1⁄6 inches long (Figure 5). ABW eggs are yellow initially but turn gray as they mature.

Pest Status

In North Carolina, annual bluegrass weevils are primarily a pest of Poa annua and creeping bentgrass but can also feed on perennial ryegrass.

Biology

Research from New York and Massachusetts indicates annual bluegrass weevil adults overwinter in treelines and other semi-protected areas on golf courses, although this has not yet been confirmed in North Carolina. Adults become active in late March to early April and females begin laying 2-3 eggs in leaf sheaths, typically in short-mown turf. Larvae emerge in mid-early April, depending on location, and develop through five instars that typically last 5-7 days each before pupating. Pupae develop for another 5-7 days before adults emerge, with the first peaks in adult activity usually occurring in early-mid May. In southwestern North Carolina, ABWs will have three generations per year, whereas in northwest North Carolina, there may only be two. Although there are some similarities in terms of ABW behavior in the northeast and the southeast, we have observed considerable differences in terms of life stage appearance timings. Adults in North Carolina appear and are active much earlier than in the northeast. Once overwintered adults have emerged, ABWs quickly cycle through three generations and most ABW activity has ceased by October. As a result, the ABW season in North Carolina is more condensed and occurs earlier in the year. This can have a tremendous impact on insecticide selection and application timing for management of this pest.

Damage

As temperatures increase in late spring, adult annual bluegrass weevils move from their overwintering sites, feed, mate, and lay eggs in the turfgrass. Adults cause damage to the turfgrass plant by chewing tiny notches in blades and although past research has stated that this does not appear to have a detrimental effect on the overall health of the turf stand, we have observed an increase in turf damage with increases in adult activity. Larval feeding consists of tiny larvae feeding within the grass stem. As they grow, they move down around the outside of the plant and into the crown. Larval damage causes small, yellow spots on short-mown turf. Early damage typically occurs in mid-May. More significant damage is observed when there is an overlap between the previous generation’s adult population and the next generation’s larval population (early-mid July and early-mid August) (Figure 6).

Monitoring

Traditional collection approaches for annual bluegrass weevil adults involve running a reverse air flow leaf blower with mesh netting attached to the front of the nozzle across the turf surface. This technique does not appear to work in areas with lower ABW populations so we recommend applying a soapy water flush (1-2 tablespoons per 1 gallon water) to a square section of the turf (2 feet x 2 feet) and wait 3-4 minutes for adults to emerge. To examine a turf stand for larvae, cut a small sample (3 inches x 3 inches x 3 inches) section from the area. Tease the tissue apart and look for all life stages. Submerge the sample in a salt-water solution (3⁄4 cup salt in 1 quart of water) for one hour.

Control

Biological Control

Some research (Vittum 1999) has shown that the beneficial nematode Steinernema carpocapsae can reduce annual bluegrass weevil populations by almost 50%. Bt has also been used to reduce larval populations by 50-65% (Vittum 2005). Spinosad can also be very effective (80% control) against larvae but only when used at a high rate. As with all control options, accurate timing is essential to successfully reducing populations.

Chemical Control

Pyrethroids (bifenthrin, lambda-cyhalothrin) are most effective against ABW adults while anthranilic diamides (chlorantraniliprole, cyantraniliprole, tetraniliprole) and an insect growth regulator (novaluron) are more effective against the larvae. Each of these insecticides may be used in a control program to target different life stages. Pyrethroid applications targeting adults should be timed when adult activity peaks.

Similar to other multivoltine insects in turfgrass, such as chinch bugs, repeated applications throughout the year can result in resistance issues if managers do not rotate insecticide classes. Resistance in ABW resulting in field control failures can build in as short as five years when the same mode of action is used exclusively and repeatedly. Once resistance has been established, the use of the pesticide that led to resistance is ineffective and can no longer be used. Furthermore, pyrethroid resistance can also lead to reduced efficacy in other insecticide classes by as much as 57% (Koppenhöfer et al. 2012) For control of ABW, pyrethroid resistance is the greatest management concern as they provide the highest and most consistent level of adult control.

| Insecticide and Formulation | Amount per 1,000 sq ft | Precaution and Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| bifenthrin (Menace, Talstar, others) F, GC | 0.25-0.5 fl oz | Monitor for adults, apply at peak activity; use GC formulation for golf courses |

| chlorantraniliprole (Acelepryn) | 0.28 fl oz | Apply appoximately 7-14 days after adulticide to target larvae |

| cyantraniliprole (Ference) | 0.28 fl oz | Monitor for adults, apply at peak activity, apply appoximately 7-14 days after adulticide to target larvae |

| indoxacarb (Provaunt) | 0.28 fl oz | Monitor for adults, apply at peak activity, apply appoximately 7-14 days after adulticide to target larvae |

| lambda-cyhalothrin (Battle, Scimitar, Cyonara) | 0.23 fl oz | Monitor for adults, apply at peak activity |

| novaluron (Suprado) | 2-2.3 fl oz | Apply approximately 7 to 14 days after adult emergence to target larvae. |

| Spinosad (Conserve SC) | 1.2 fl oz | Monitor for adults, apply at peak activity. |

| Tetraniliprole (Tetrino) | 0.367-0.735 fl oz | Apply approximately 7 to 14 days after adult emergence to target larvae. |

|

zeta-cypermethrin, bifenthrin, and imidacloprid (Triple Crown) |

0.57-0.8 fl oz | Monitor for adults, apply at peak activity. |

ABW IPM Recommendation

Monitoring for annual bluegrass weevil is an essential part of a successful management program, particularly in North Carolina. Because this insect is not fully established in some areas, when sampling at sites that are relatively close to each other (< 15 miles apart), you may notice a big difference in emergence timing, population size of ABW life stages, and damage intensity. Therefore, proximity to a golf course that may or may not be spraying for ABW should not dictate the application timing for a nearby site. Depending on where you are located, insecticide application timings may need to be adjusted by a week or two in order to maximize product efficacy. Keep a map of areas of past damage, apply a soapy water flush to these areas weekly, and keep track of adult numbers over the growing season. When these numbers start to increase, plan your application approach and select the most effective product for that life stage.

References

Annual bluegrass weevil: a metropolitan nightmare. Vittum, P. J. 1999. Turfgrass Trends 8 (5): 1-6.

Biology and Control of the Annual Bluegrass Weevil. Koppenhöfer, A. and B. McGraw. 2016.

Evaluation of Insecticides on Hyperodes spp, a pest of annual bluegrass turf (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Tashiro, H., et al. 1977. Journal of Economic Entomology 70: 729-733.

Seasonal Activity of Listronotus maculicollis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) on Annual Bluegrass. Vittum, P. J., and H. Tashiro. 1987. Journal of Economic Entomology 80: 773-778. https://ncturfbugs.wordpress.ncsu.edu/homepage/

Turfgrass Insects of the United States and Canada, 2nd ed. Vittum, P.J., M.G.Villani, and H. Tashiro. 1999. Cornell University Press, NY. 422pp.

Vittum, P. 2005. Annual bluegrass weevil: A metropolitan pest on the move. Golf Course Management. May 2005. p 105-108.

- 2018 Pest Control for Professional Turfgrass Managers. Bowman, D. et al. 2017. NC State Extension Publication AG-408. 81 pp.

- Extension Plant Pathology Publications and Factsheets

- Horticultural Science Publications

- North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual

For assistance with a specific problem, contact your local Cooperative Extension Center